by: Milagros Vidal

Text:

«quem ocupa cuida»

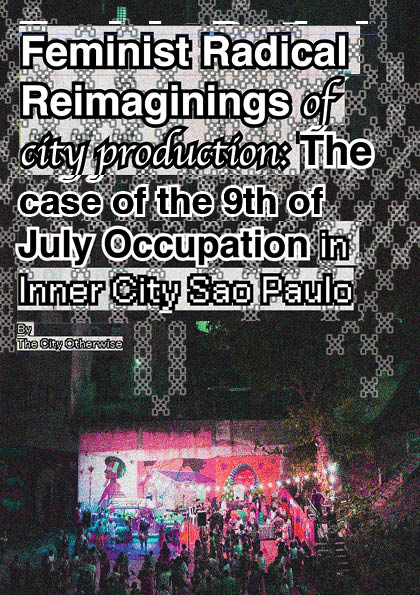

In the shadow of São Paulo’s towering skyscrapers and ever-expanding urban fabric lies a story of rebellion and care. Amidst this complex urban landscape, new ways of imagining urban space are emerging. Black women-led housing occupations are occupying abandoned buildings in the city center.

They are not just about securing shelter or housing, they’re about transforming the way cities are produced, envisioning alternative urban futures grounded in spatial and racial justice, self-determination, inclusion, and solidarity. It is not just about claiming geographical and political centrality but also about reimagining how we live, interact, treat, and support one another. Through collective living and the centralization of reproductive labor these movements resist systemic oppression, reimagine new ways of relating to one another and materialize the city otherwise.

inequality by design

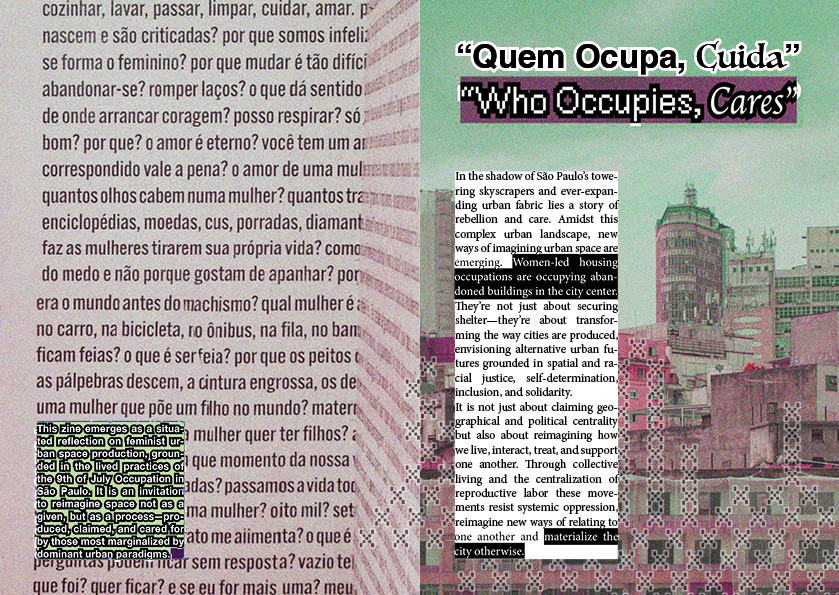

Cities are not neutral—they are intentionally designed. Whether through masterplans drawn by white men behind closed doors or through every day decisions and acts shaped by capitalist logics rooted in class, gender and racial hierarchies, urban spaces are designed to privilege some while marginalizing others.

The rise of capitalism was possible due to the systematic subjugation of women, particularly in their reproductive roles. This subjugation relegated women to the private sphere, confining them to the home and reproductive tasks and isolating them from public and political spaces, separating them from collaborative networks and rendering them more vulnerable to violence. The history of capitalist city-building reflects this binary logic, prioritizing productive spaces over reproductive ones. This division becomes especially unbearable as women have to navigate both spheres under conditions of scarce resources, precarious employment and unstable housing.

In Latin America, rapid urban development has often come at the expense of marginalized groups, exacerbating poverty and precarity among those defined by their gender and race. Yet this adversity has also catalyzed the rise of vibrant, women-led social movements. Women, trans, lesbians, and other marginalized bodies are at the frontline of this change—because they are the most affected by dispossession and precarity, they have also become the greatest force for social transformation in Latin America.

WITCHES AND SPACE PRODUCTION

To produce other forms of space, we must develop new ways of thinking. Feminist urban thought begins with a refusal: a refusal of objectivity as neutrality, of space as passive scenery, of the home as apolitical. As Haraway, Crenshaw and Gonzales remind us, all knowledge is situated, embodied, and shaped by intersectional experiences of gender, race, and class. Feminist space production embraces this multiplicity. It is not just about conceptualizing cities for and by women and other bodies, but about creating cities that are inclusive, diverse, and multicultural. It asks: what kinds of urban life become possible when we center reproductive labor? When we treat care as a foundational act of spatial creation?

These space and practices are already emerging—in the shadows and in the light, in the peripheries and in the center, in occupations of land or buildings, in the house and in the streets, in communal gardens and kitchens. In these spaces, women, lesbians, and trans people assert not only a right to housing, but the right to the city, the right to citizenship, and the right to refuse.

AMOR E CUIDADO: SAO PAULO

Despite its economic power, international influence and wealth Brasil is within the top ten countries in the Gini scale of the highest income inequality. This deep inequality is reflected on gendered and racialized bodies. In Brasil, Black and brown women spend more time in care and reproductive work while they also participate less in the labor market and are therefore more affected by poverty. Women have more precarious jobs, earn less, are more prone to informal jobs and are very unrepresented in the political scene.

In São Paulo, Brazil’s largest city and one of the ten largest metropolitan areas in the world, home to over 20 million people, an intriguing urban paradox unfolds—monumental buildings in the city center stand abandoned while the city continues to expand horizontally. While thousands sleep on the streets or live in precarious conditions on the city’s outskirts countless buildings in the city center sit empty, held hostage by speculative markets and private interests.

Since the 1980s, under the rallying cry of the “Right to the City,” social and housing movements took to the urban heart of the city. Many iconic empty buildings of the city center are now occupied by social movements, serving not only as temporary housing but also as a political statement demanding government action on housing and land access. These empty buildings scattered throughout the city become stages of opportunity, where their abandonment leaves room for urban experimentation.

The occupation phenomenon has been accompanied by the rise of women in leadership roles within housing movements. Women leaders have framed the claim to housing as a gendered issue through intersectional struggles based on race, gender and class. This alignment of housing movements with feminist movements has turned occupations into spaces that condense both the housing and gender equality struggle. The majority of members within occupations are women and their children. Many are seeking refuge and community, some having fled from domestic violence.

These communal living situations ensure more than just survival; they become spaces where new forms of citizenship, political engagement, self-determination, and activism emerge. The political radicalization of these groups is rooted in the understanding of capitalism and its reliance on social divisions as the main drivers of precarity, marginalization, and poverty. Women recognize themselves as key actors in the urban struggle because, despite being marginalized by the system, it is their unpaid reproductive labor that sustains the cities of today.

Ocupação 9 de Julho

On September 30, 2016, members of the Movimento Sem Teto do Centro (MSTC) reclaimed an abandoned building in central São Paulo. Led by Carmen Silva (MSTC leader) a Black woman, mother and survivor of gender violence, the act was more than protest—it was a manifesto for another way of living. The day of the occupation, also known as Dia de Festa, marked not just a seizure of space, but the beginning of a new social contract rooted in cooperation, safety, and shared responsibility.

After nearly eight years of occupation, the building has now become not only a flagship for the movement, serving as the headquarters of MSTC, but also an exemplary form of occupation of inner city areas. The occupation is renowned both nationally and internationally, housing not only 122 families but also the famous solidarity kitchen. The MSTC phrase “those who occupy, care”, which emerged during the pandemic, is present in all practices-spaces of the occupation, emphasizing that the act of occupying is inherently tied to the act of caring, both for people, buildings and the environment. In the 9 de Julho Occupation, occupying and caring are so tightly bound that they become synonyms.

mutirão and conscientização política

From day one, mutirão — mutual aid— was fundamental. In the absence of state support, it is mutual aid that builds the walls, connects the water, cooks the food, distributes roles, mediates conflicts, and educates children. Women play a central role in this organizational infrastructure. They are the leaders, coordinators, and caregivers. They are also the architects of a political practice that begins with care and extends toward citizenship claims and political participation.

“You need rules to occupy,” says Ana, a long-time MSTC member. From allocating space to creating internal statutes, everything is negotiated collectively. Floors are organized, roles assigned, and decisions made through assemblies. Support teams span from health, security, construction, culture, to childcare and LGBTQ+ rights. Through this deeply structured yet flexible governance model, the occupation becomes both a refuge and a site of transformation.

But organization alone is not enough. The movement insists on political awareness as a core practice. For Carmen Silva, eating, living, and surviving are all political acts, yet to fight for systemic change, people must also understand policy, law, and the constitution. The movement cultivates this awareness in everyday life—through discussions, Sunday lunches, mobilizations, and spaces of shared and critical reflection.

Their work is not about charity or aid. It is about power. Women like Bruna, who once felt excluded from public life, now educate others on their rights. Women like Preta Ferreira, Carmen’s daughter, use art and culture as tools for radical pedagogy. Within these walls, members transform personal pain into collective strength. The private becomes political. The house becomes a commons. It is not just shelter—it is a feminist pedagogy of resistance.

BUILDING COMMONS

At the 9th of July Occupation, space is not fixed—it is alive. It shifts daily through collective action, negotiation, and need. Residents do not simply live within walls—they transform them. Feminist spatial practice here is a continuous process of undoing and remaking. It is about challenging the spatial logics inherited from patriarchy, capitalism, and colonialism. It questions the architecture of the nuclear family, the invisibility of reproductive labor, and the confinement of care to the private domain. Instead, it insists that space can hold multiplicity—that it can be shared, reclaimed, and politicized from the ground up.

THE KITCHEN

Just as the kitchen is the heart of a home, the kitchen is the heart of the 9th of July Occupation. It is one of the first common spaces to be founded and rehabilitated when a building is occupied. But the Cozinha Ocupação 9 de Julho is more than a kitchen for residents. It became one of the movement’s most important activities during the COVID-19 crisis. From this space, hundreds of lunch boxes are prepared and distributed to unhoused people in downtown São Paulo. This work is funded through the occupation’s most iconic event: the Sunday lunches.

THE SUNDAY LUNCHES

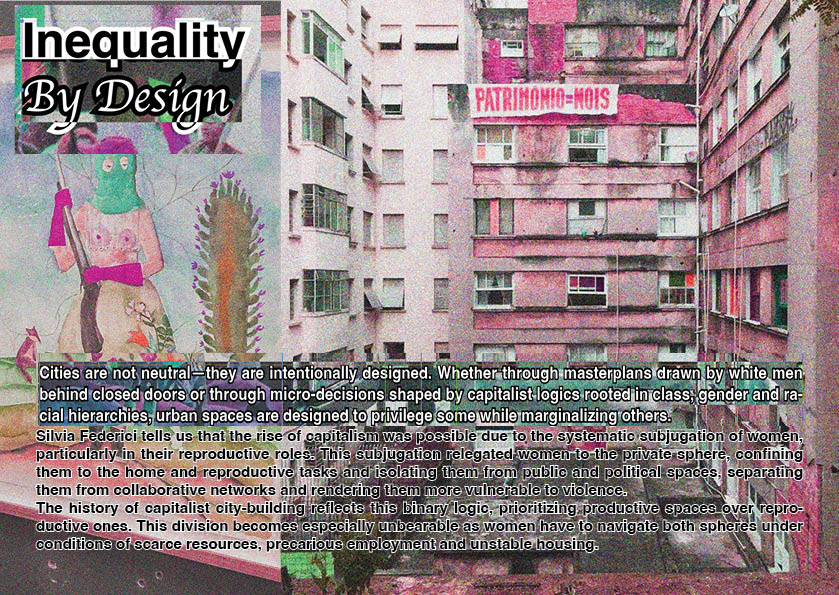

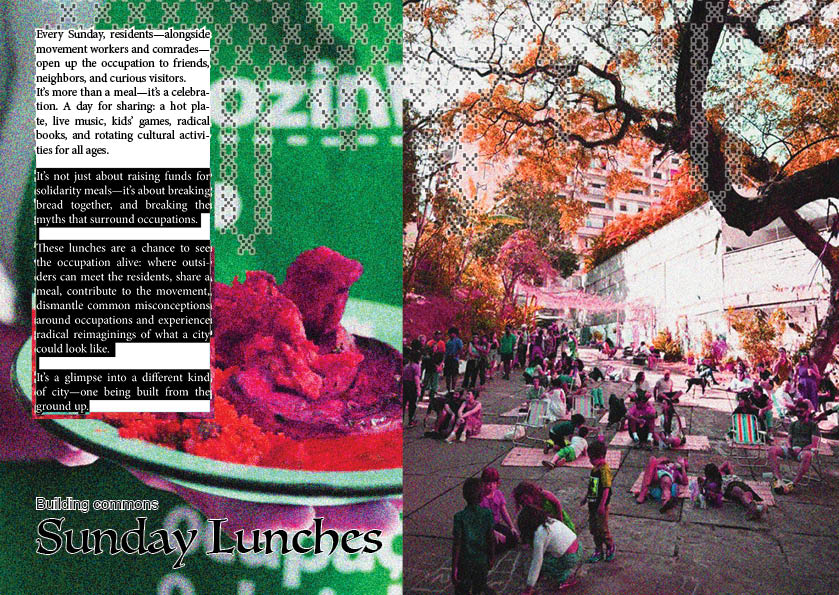

Every Sunday, residents—alongside movement workers and comrades—open up the occupation to friends, neighbors, and visitors. It’s more than a meal, it’s a celebration. A day for sharing: a hot plate, live music, kids’ games, radical books, and rotating cultural activities. It’s not just about raising funds for solidarity meals—it’s about breaking bread together, and breaking the myths that surround occupations. These lunches are a chance to see the occupation alive: where outsiders can meet the residents, share a meal, contribute to the movement, dismantle common misconceptions around occupations and experience radical reimaginings of what a city can look like.

THE GARDEN

The Garden operates in close connection with the kitchen. While not all the food served at the Sunday lunches originates there, all organic waste from meals is composted and returned to the soil as fertilizer. The garden was born from a collective decision—a shared desire to cultivate life where there was once only debris. Izabel, once the building’s doorkeeper and originally from a farming family in Brazil’s interior, envisioned what that empty space could become, seeing potential where others saw abandonment. Alongside other residents, she cleared rubble, revitalized the soil, and planted the first seeds. Today, the garden spans roughly 300m². It produces vegetables, herbs, and compost. It nurtures surrounding trees. It is a green rupture in a city dominated by concrete.

But the garden is more than functional—it is pedagogical, poetic and political. It is a space where the community learns to plant, where land-based knowledge is shared and where care becomes a visible and performative collective act. In a city where land is scarce and speculation is pervasive, cultivating a garden becomes a slow, deliberate refusal. It refuses dispossession. It refuses isolation. It refuses speed. It insists on rootedness, on collaboration, on interdependence and the slowness of collective process.

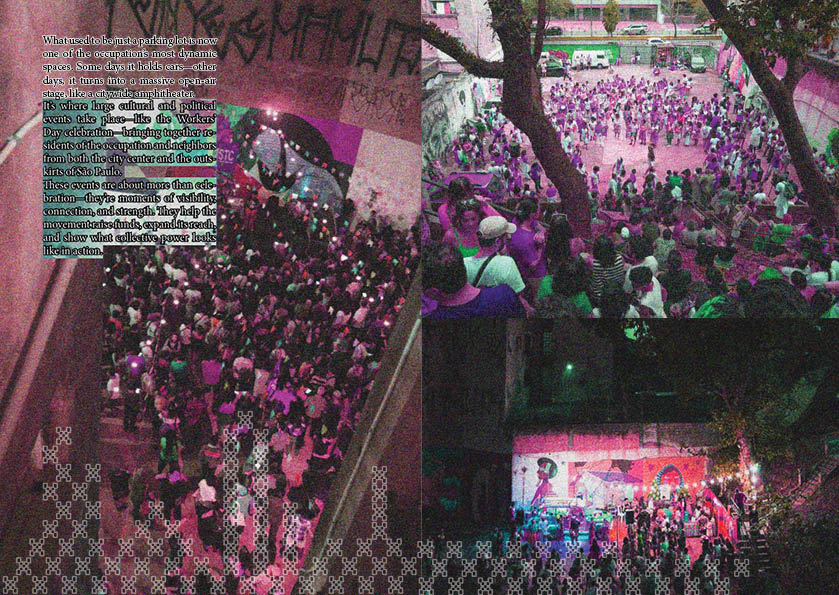

THE OUTDOORS

The outdoor grounds of the occupation are more than just leftover space—they’re where everyday life and collective encounter happen. Four walls with no roof form a large open-air theatre, a sort of citywide amphitheater covered with graffiti. This is where Sunday lunches happen, but also where fairs pop up, where concerts, plays, film screenings, and political rallies come to life. These outdoor areas are open, alive, and constantly shaped by the people who use them. They’re part of what makes the occupation not just a shelter, but a space for life, resistance, encounter, and joy.

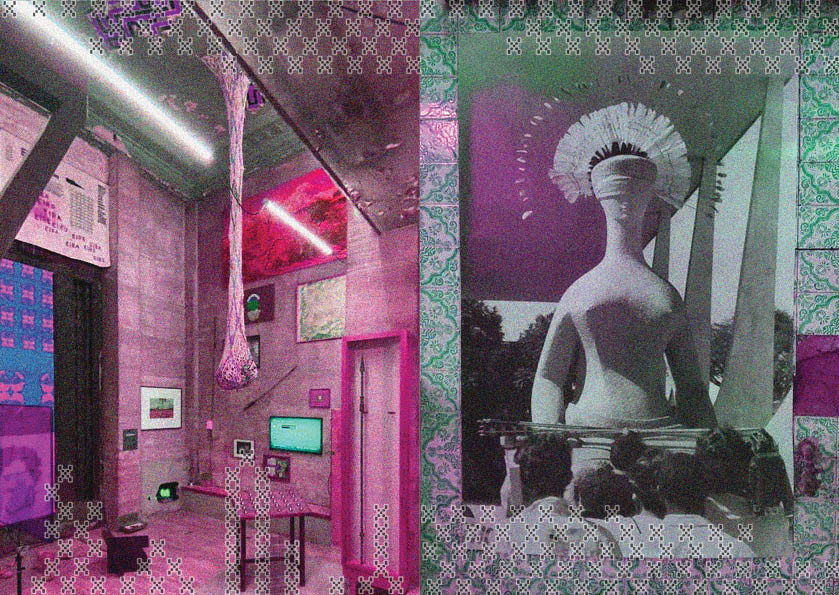

THE ART GALLERY

“Culture is freedom; culture is a pillar of housing.” – Preta Ferreira

For the MSTC, culture is not a luxury—it’s a political necessity. Culture is a means of reclaiming visibility, building collective identity and history. In the movement’s vision, the right to housing is deeply connected to the right to culture, to memory, to self-expression and self-determination. Tucked inside the occupation, the Re-Ocupa art Gallery is where art meets struggle. It’s an autonomous exhibition space run by residents and allies, dedicated to showcasing Black feminist, decolonial, and emancipatory art. The gallery features rotating exhibitions—paintings, photography, installations, posters, and more—by artists from within the movement and from across São Paulo and the region. But it’s more than a gallery. It’s a space for workshops, talks, screenings, and conversations.

THE COMMON FLOOR

The common room is one of several shared spaces on the third floor—but it holds a special place in the history of the occupation. It was the first room to be rehabilitated, and the space where everyone slept together during the critical first 72 hours of the occupation. After those tense initial days, residents began exploring and restoring the rest of the building, collectively deciding how to distribute rooms and define the use of each space. But this process could only happen through negotiation, self-organization, and care. The common room is where those early decisions were made—where debates unfolded, votes were cast, and the foundations of collective life were built. Today, it’s still where residents gather for monthly assemblies and political meetings.

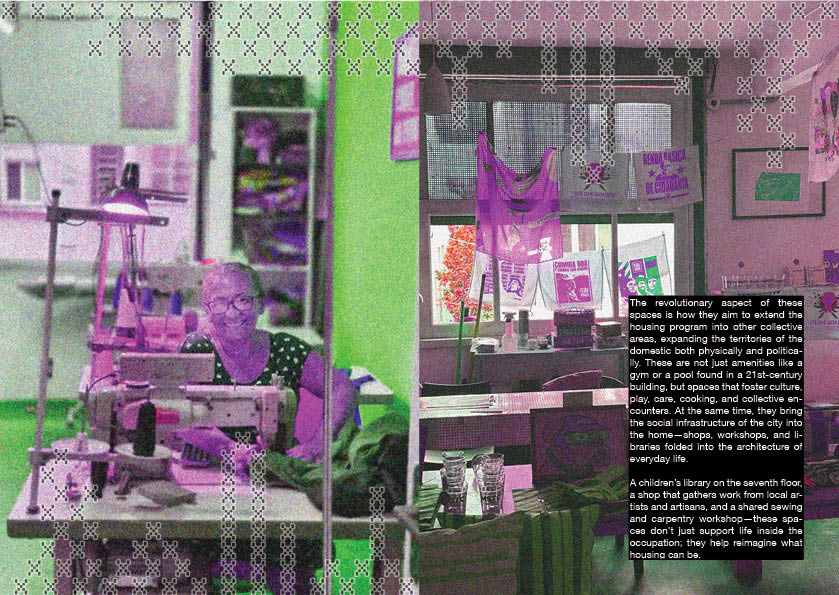

The revolutionary aspect of these spaces is how they aim to extend the housing program into other collective areas, expanding the territories of the domestic both physically and politically. These are not just amenities like a gym or a pool found in a 21st-century building, but spaces that foster culture, play, care, cooking, and collective encounters. At the same time, they bring the social infrastructure of the city into the home—shops, workshops, and libraries folded into the architecture of everyday life. A children’s library on the seventh floor, a shop that gathers work from local artists and artisans, and a shared sewing and carpentry workshop—these spaces don’t just support life inside the occupation; they help reimagine what housing can be.

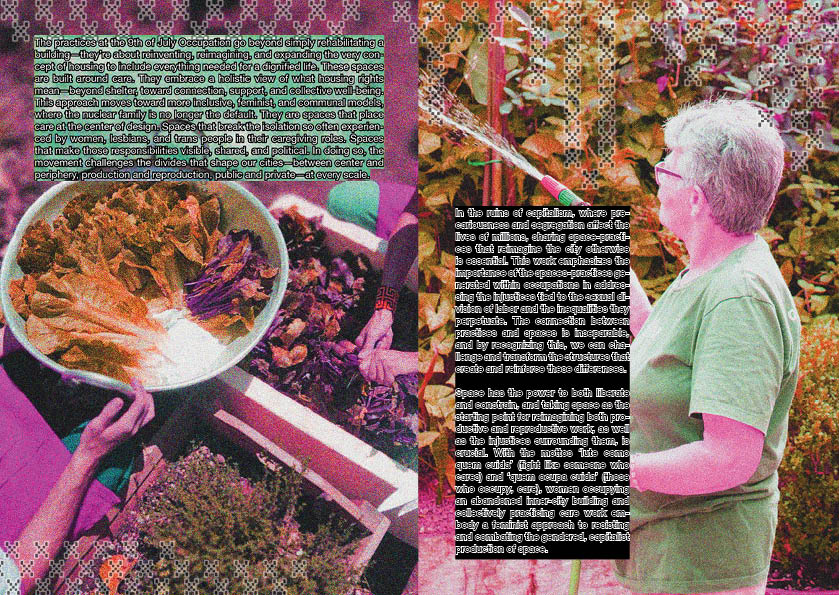

LUTE COMO QUEM CUIDA

The practices at the 9th of July Occupation go beyond simply rehabilitating a building—they’re about reinventing, reimagining, and expanding the very concept of housing to include everything necessary for a dignified life. These spaces are built around care. They embrace a holistic view of what housing rights mean—beyond shelter, toward connection, support, and collective well-being. This approach moves toward more inclusive, feminist, and communal models, where the nuclear family is no longer the default. They are spaces that place care at the center of design. Spaces that break the isolation so often experienced by women, lesbians, and trans people in their caregiving roles. Spaces that make those responsibilities visible, shared, and political. In doing so, the movement challenges the divides that shape our cities—between center and periphery, production and reproduction, public and private—at every scale.

In the ruins of capitalism, where precariousness and segregation affect the lives of millions, sharing space-practices that reimagine the city otherwise is essential. This work emphasizes the importance of the spaces-practices generated within occupations in addressing the injustices tied to the sexual division of labor and the inequalities they perpetuate. The connection between practices and spaces is inseparable, and by recognizing this, we can challenge and transform the structures that create and reinforce these differences.

Space has the power to both liberate and constrain, and taking space as the starting point for reimagining both productive and reproductive work, as well as the injustices surrounding them, is crucial. With the mottos ‘lute como quem cuida’ (fight like someone who cares) and ‘quem ocupa cuida’ (those who occupy, care), women occupying an abandoned inner-city building and collectively practicing care work embody a feminist approach to resisting and combating the gendered, capitalist production of space.

Deja un comentario